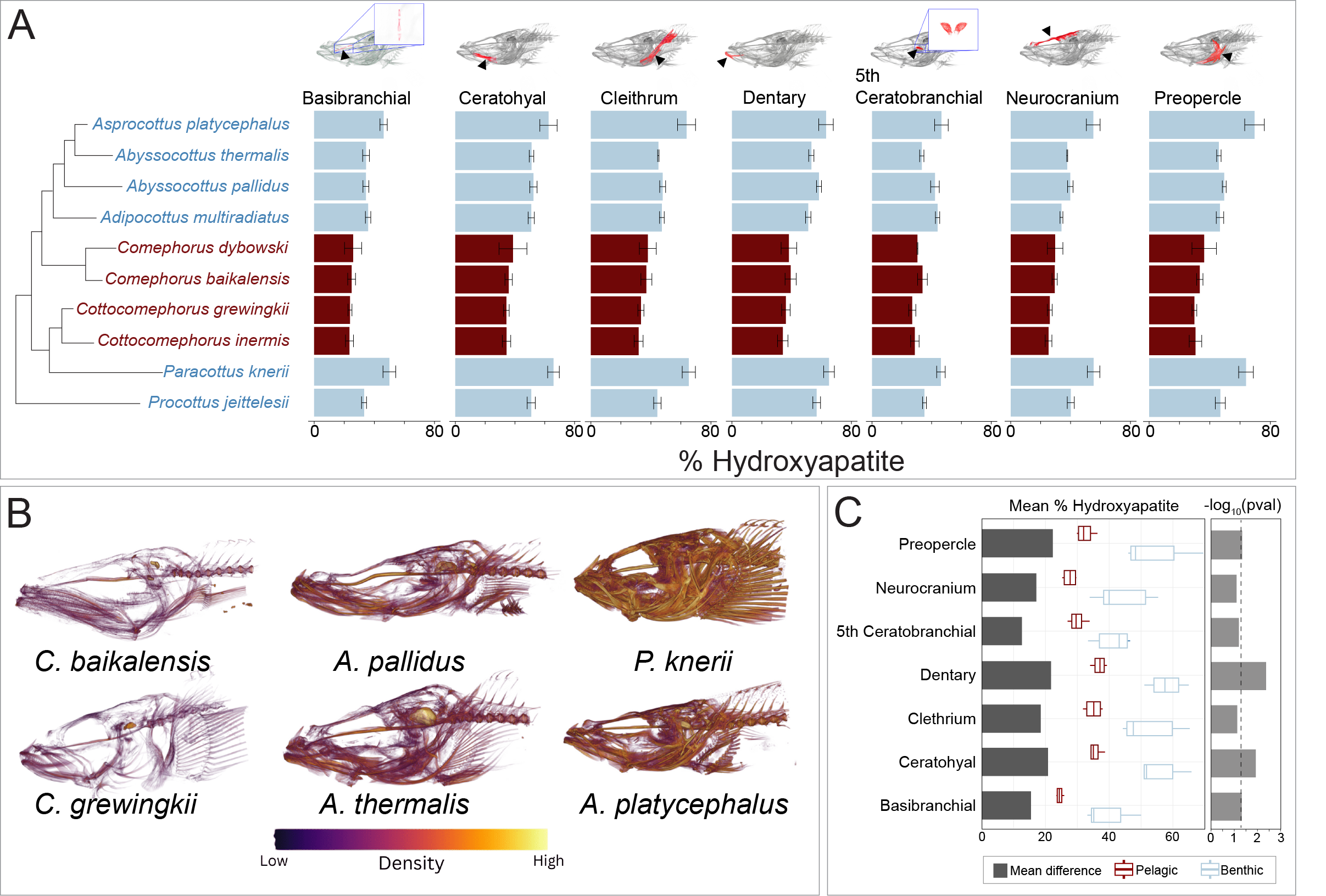

Habitat transitions are a major driver of morphological evolution. Teleost fishes have repeatedly transitioned from benthic to pelagic habitats, often evolving predictable changes in body shape that enhance hydrodynamic efficiency. While freshwater sculpins (Cottidae, Perciformes) are usually benthic, two genera in Lake Baikal, Comephorus and Cottocomephorus, have independently evolved into midwater niches. As sculpins lack a swim bladder, these lineages instead improved buoyancy through reduced skeletal density and increased lipid stores. Using micro-computed tomography and two-dimensional morphometrics, we characterized skeletal evolution across the Baikal sculpin radiation. We found that parallel changes in bone mineral density and microstructure independently evolved in the two pelagic clades. Density reductions occurred throughout the skull in pelagic species. The basibranchials and neurocranium exhibited the lowest overall bone density across all cranial elements. While the jaws maintained the highest absolute density values among the bones we measured, they also showed the greatest proportional reduction in density associated with pelagic habitat use, with a 56.86% decrease in percentage hydroxyapatite and a 21.39% increase in porosity. Morphometric analyses further identified convergence toward an elongate body shape, reduced and posteriorly shifted eyes, and elevated fin insertion in pelagic taxa. These results demonstrate a repeated skeletal lightening and body shape changes accompanying benthic-to-pelagic transitions. This pattern mirrors other benthic-to-pelagic transitions in teleosts that lack swim bladders, highlighting shared biomechanical and microstructural solutions to life in the open water.

Convergent reduction in skeletal density during benthic to pelagic transitions in Baikal sculpins

Gutierrez BA, Larouche O, Loetzerich S, Gerringer ME, Evans KM, Aguilar A, Kirilchik S, Sandel MW, Daane JM

2026.

bioRxiv doi:10.64898/2026.01.22.701097.